Prelude to the desktop content graph project

Following my recent series of articles on building a content graph (based on content in web content management systems), I thought that it would be interesting to explore doing something similar for managing desktop content (that is, content in files on a local computer). If you've read other things that I've written, you may recall that I am a bit of an advocate for content being managed as objects rather than encapsulated in platform-specific files. But I can't ignore the fact that most of the world uses their content in just that way, me included. Files are everywhere, and even in a landscape of growing importance of social media and podcasts, files are where most of our content resides. So I've been thinking about what is possible in terms of better management.

Anyway, I've explored this in a series of articles dealing with designing and building a system that I've called the Desktop content graph. The articles cover design of an information model for files, design of processes for linking files together, classification of files using a taxonomy based on file system tags, and design and build of a desktop application to manage the processes.

This article sits outside the timeline of the others; here I'm trying to set the scene and to state the problems that I'm hoping to address. Numerically it's really part 0.

- Part 0 Setting the scene (this article)

- Part 1 The model for the Desktop content graph

- Part 2 Tags and taxonomy concepts

- Part 3 Building the initial Desktop content graph system

I started to think about how I manage files at the moment so that I can position them in context with other files, and to be able to find them again later. To cut a very long story short, I don't manage things very well. I tend to use folder structures based on whatever is uppermost in my mind at a given moment (usually a business project), together with file-based applications such as Word and Excel. The nearest that I get to linked data is to group files related to the project into a common folder for that project. The myriad of resulting problems include the typical ones that all knowledge workers encounter:

- I continually lose track of files. I don't use filenames very effectively to unambiguously identify files (and actually, that's deliberate; filenames are terrible identifiers, because they are impermanent and lack the namespace for effective naming).

- I'd like to be able to have metadata attached to files to tell a forgetful me in the future something about the context in which I did the work. I can't do this.

- It's hard to have a file in more than one folder (without copying it, which defeats the object). What do I do if this file properly belongs in both of these folders? BTW I know that aliases do this to a degree in MacOS, but that is a fragile mechanism.

- I'd like to re-use information from existing files when a new piece of work arrives.

- I can't classify my files. I'd really like to have a taxonomy that lets me tag files against one or more concepts, and lets me in effect link files together by virtue of a common profile of tags.

Search engines, you say? If you have previously read my articles you will know that I am no fan of full-text search engines. It may seem perverse, given that these tools are ubiquitous, and indeed I use them just like everyone else.

But search engines are blunt instruments, and they suffer from the dual problems of poor precision and little capacity for handling information structure. Operating systems don't do much to help here; for example MacOS allows you to tag files in the Finder. but you can't search for tags using Spotlight. There are some commercial tools to help you to find files by file name (Find Any File and HoudahSpot on the Mac, for example). There are other applications that allow you to build content databases (that is, applications that allow you to search for content within files). These are mostly file organisers with (sometimes) internal indexing; I've tried many such applications over the years, including StickyBrain, SOHO Notes, Lotus Agenda, Yojimbo, Obsidian, and Devonthink. I'm just going to talk in detail about the last of these, which is the one I use most of the time now. But as you'll see, even the best of a mediocre bunch doesn't go very far in solving my information problems.

Beyond finding content, even if you can find your stuff, it's next to impossible to link content in files to other content. Actually, I see this as an opportunity as much as a problem; if the operating system and file system don't provide the tools and structures to manage things, then it seems like an invitation to work over the top of these systems and manage information independently of the operating system and applications.

Tools for managing files and content

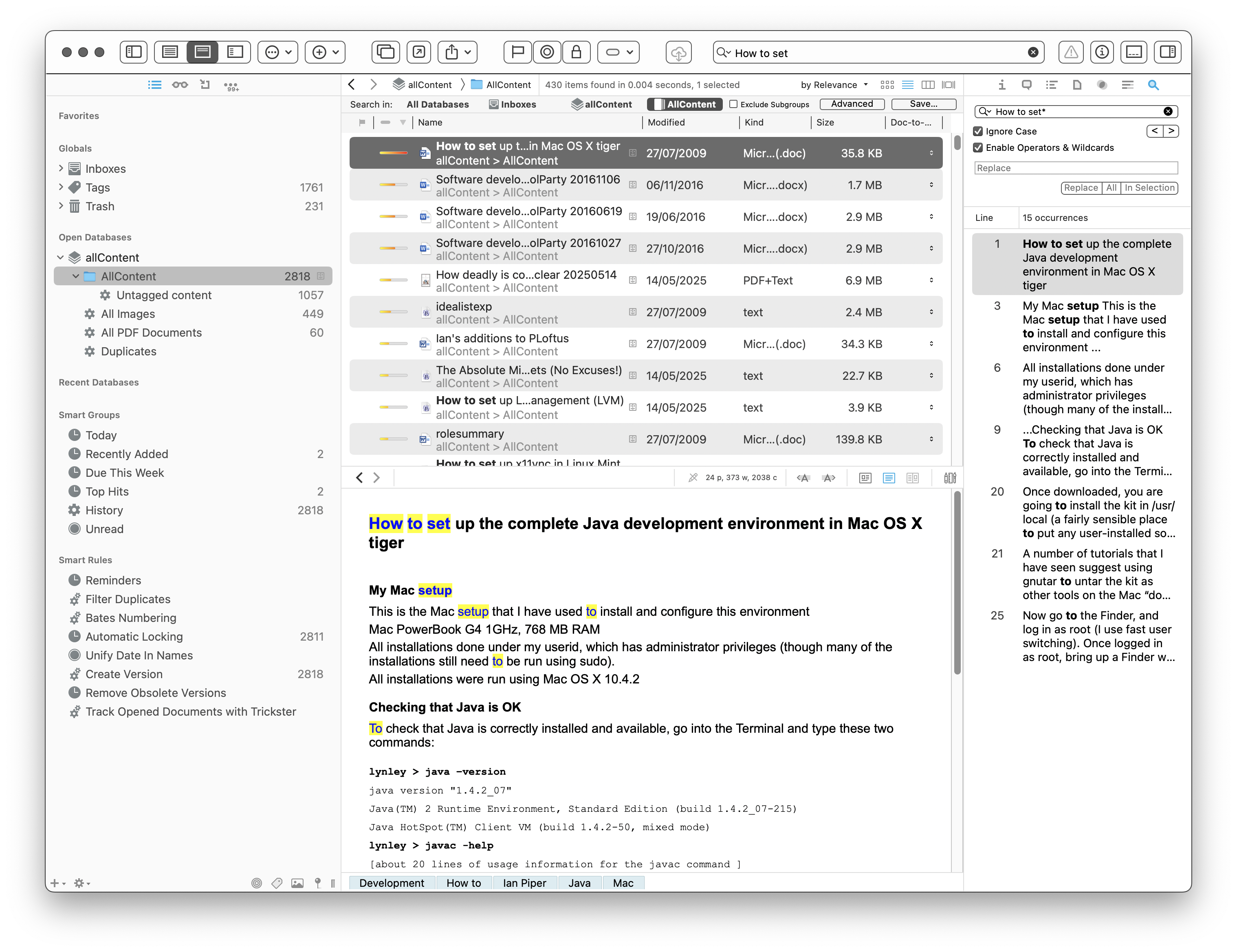

Devonthink 3

This is one of the leading information management tools available for the Mac. It is a kind of file-based content database with, in addition to full-text indexing, support for tagging using Finder tags and a lot of (too complex for me) other support tools. When you import (or index) documents into Devonthink it will look for Finder tags and apply them within the program. One of the navigation mechanisms is by tag, so it's easy to find which content items have been tagged with a Finder tag.

Devonthink is also useful in terms of the breadth of content types that it will handle. As well as text, it works well with rtf(d), pdf, MS Office and LibreOffice files, various graphics formats and many others.

Devonthink has one other design feature that works particularly well for me. You can use the program in two different modes, with the content held either internally or externally. With an internal database, you import documents into the program's database. From this point on, the original file is not used by Devonthink; instead, the indexing and general management of the content happens within the Devonthink database, which is basically a single large file.

If you prefer, you can manage your Devonthink content externally. In this case, you simply point the indexer at the content in the file system and Devonthink indexes it. The content itself stays untouched in the file system. This approach works well for me, because it's the lightest touch approach; the file content is still usable exactly as it was before Devonthink indexed it. So this is how I use Devonthink. I don't use more than a tiny proportion of its features; to be honest, it feels rather over-engineered. Take a look at the screenshot below to see just how complex the user interface gets. I will, in passing, note one of its irritating features. Yes, it's the search tools. There are two different search fields available, without much of a hint as to which you should use in which circumstances.

Returning to tagging, in the final analysis, we are still just talking about text-based tagging; simple keywords (here is an article on why taxonomies are better than keywords). I would like to see a classification taxonomy as an information structure in its own right. This is a core design principle of the Desktop content graph, as I will show in a later article. To begin with I'm going to look at how we might make it easier to link file objects together, and then how to make tagging a bit more straightforward and useful.

A trip down the rabbithole; Finder tags

Here is a brief diversion down the rabbithole on tags in the MacOS Finder. Take a look, if you're interested, then come back to continue from here.

Tools for building links between things

Turning to existing tools for linking information; this is quite a limited field. The simple fact is that operating systems are not very good at linked data. As you will see, for the Desktop content graph system that I'm building I'm having to create a linked data layer over the file system. That said, there are a couple of interesting tools available.

Hookmark

This is a program that lets you build links between files, web links and emails. Once installed on a Mac (Mac only, I'm afraid) you can activate it with a hot key. You can then nominate the source file and/or the destination file, and Hookmark will create a link (which it calls a hook). It has a bespoke link structure and a rather unusual user interface. Actually, I find the user experience too difficult to understand and so I have given up on using it.

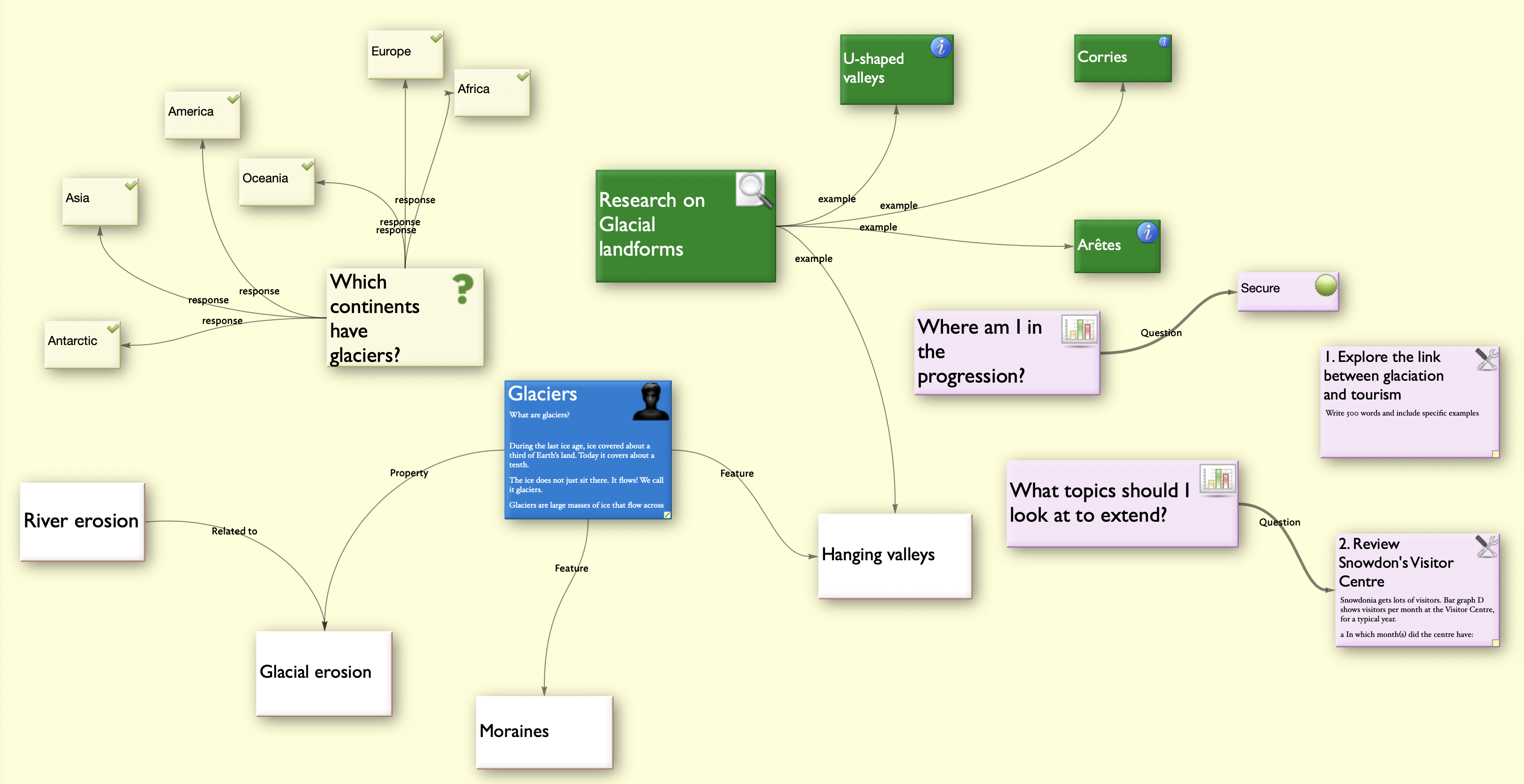

TinderBox

TinderBox is aimed more at information management than file management. It has a sophisticated and complex user interface based on a workspace visual metaphor. TinderBox is also blessed with an unusual user interface.

From my exploration of the program, it does not seem to have file handling features. It does have a variety of options for building links, but there is no underlying model as far as I can see. Anyway, I'm afraid that I've dropped this application too.

There really is no existing application that lets me create a Desktop content graph. Maybe that indicates that I'm tilting at windmills; if it's such a good idea, why hasn't anyone already done it? Well this is an argument that I've heard over my entire career against doing anything new, and it makes me grind my teeth in frustration. If you take that argument on faith, nothing would ever have been invented; the fact that something doesn't exist yet may just mean that there's an unmet need.

In any case, it's important to me to explore this idea, and that's enough of a reason, enough of an excuse.

In the next article I'm going to describe the process of designing the information model that will be needed to support a Desktop content graph.

I hope that you will read along.